Steve Garvey

| Steve Garvey | |

|---|---|

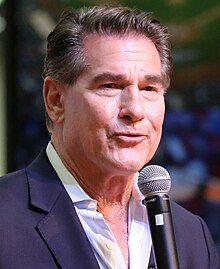

Garvey in 2016 | |

| First baseman | |

| Born: December 22, 1948 Tampa, Florida, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 1, 1969, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| May 23, 1987, for the San Diego Padres | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .294 |

| Hits | 2,599 |

| Home runs | 272 |

| Runs batted in | 1,308 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Non-MLB stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Steven Patrick Garvey (born December 22, 1948) is an American former professional Major League baseball player who played first baseman for the Los Angeles Dodgers and San Diego Padres from 1969 to 1987.

Garvey began his major league career with the Dodgers in 1969. He won the National League (NL) Most Valuable Player Award in 1974 and was the National League Championship Series MVP in 1978. Garvey was also a member of the 1981 World Series-winning Dodgers.

Garvey signed with the Padres in December 1982 and remained with the team until 1987, when his playing career ended. In 1984, Garvey was once again named a National League Championship Series MVP; he hit a dramatic walk-off home run to win Game Four of the Championship Series for the Padres. Garvey was a National League All-Star for ten seasons, with nine selections as starter at first base, a mark that still stands for his position.[1] He holds the NL record for consecutive games played with 1,207. The Padres retired Garvey's No. 6 in 1988.

During his time as a baseball player, Garvey also served as vice president of the philanthropic organization No Greater Love.[2]

In October 2023, Garvey announced his candidacy as a Republican for U.S. Senate from California in the 2024 election for the term starting in January 2025. He finished a close second in the March 2024 top-two primary, 3,478 votes behind Democratic Congressman Adam Schiff, advancing them both to the general election.[3] Garvey finished first in the partial-term special-election primary to replace Laphonza Butler with that term ending in January 2025. He faced Schiff in that election, and lost.[3][4]

Early life

[edit]Garvey was born in Tampa, Florida, on December 22, 1948,[5] to parents who had recently relocated from Long Island, New York.[6] Garvey is Irish-American on his father's side; his father's roots come from County Cork, Ireland.[7]

From 1956 to 1961, Garvey was a batboy for the Brooklyn Dodgers, New York Yankees and Detroit Tigers during spring training. He graduated from George D. Chamberlain High School in 1966.[8] At Chamberlain, he was a teammate of future Major Leaguers Tom Walker and Mike Eden.[9]

Michigan State University

[edit]After graduating from Chamberlain High School, Garvey played football and baseball at Michigan State University. He was committed to play football and baseball in college despite being drafted in the third round by the Minnesota Twins in the June 1966 amateur draft at age 17.[10] Garvey credited his choosing MSU to Spartan head football coach Duffy Daugherty's encouraging him to be a multi-sport athlete.[11]

At MSU, Garvey recorded 30 tackles and earned a letter as a defensive back in 1967.[12] His first at-bat in a Spartan uniform resulted in a grand-slam home run, with the ball landing in the Red Cedar River.[13] Garvey continued to work towards completing his degree after beginning his professional baseball career, and in 1971 he received a Bachelor of Science in health and physical education.[14][15]

Garvey was named Michigan State Baseball Distinguished Alumnus of the Year in 2009,[16] he was inducted into the Michigan State University Hall of Fame in 2010,[12] and his baseball jersey number 10 was retired from Michigan State University in 2014.[17]

Major League Baseball career

[edit]Los Angeles Dodgers

[edit]Garvey was drafted by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1st round of the 1968 MLB draft (June secondary phase).[18] He made his Major League debut on September 1, 1969, at the age of 20.[18] He appeared in the 7th inning to pinch hit for Ray Lamb and struck out in his one appearance at the plate.[19] He had two more plate appearances in 1969 as a pinch hitter and recorded his first hit on September 10, off Denny Lemaster of the Houston Astros. He played third base for the Dodgers in 1970 and hit his first home run on July 21, 1970, off Carl Morton of the Montreal Expos. He moved to first base in 1973 after the retirement of Wes Parker.

Garvey was part of one of the most enduring infields in baseball history,[20] along with third baseman Ron Cey, shortstop Bill Russell, and second baseman Davey Lopes. The four infielders stayed together as the Dodgers' starters for eight and a half years, starting on June 13, 1973.[21]

Garvey is one of only two players to have started an All-Star Game as a write-in vote, doing so in 1974. That year, he won the NL MVP award and had the first of six 200-hit seasons. In the 1978 National League Championship Series, which the Dodgers won over the Philadelphia Phillies, Garvey hit four home runs and added a triple for five extra base hits, both marks tying Bob Robertson's 1971 NLCS record and earning him the League Championship Series Most Valuable Player Award; Jeffrey Leonard would tie the NLCS home run record in the 1987 NLCS.

Garvey's cheerful personality, his availability with reporters, and his willingness to sign autographs for fans made him a very popular player, and the Dodgers took advantage of this, making him one of the main focuses of their public relations campaigns. This caused friction with some of his Dodger teammates, such as Cey and Lopes, who thought Garvey was only acting this way to get endorsement opportunities. Cey, Lopes, and another unnamed player criticized Garvey in a mid-June 1976 San Bernardino Sun-Telegram article, which prompted manager Walter Alston to call a team meeting. At this meeting, Garvey said, "If anyone has anything to say about me, I want it said to my face, here and now."[22] No one said anything. Tommy John thought it was at this point that Alston, who retired at the end of the year, began to lose control of the team.[23]

Late in the 1978 season, the rift resurfaced when The Washington Post published an article in which Don Sutton was quoted complaining that Garvey was the only Dodger to get publicity, and insisting that Reggie Smith was a better player.[24] The day after the article appeared, Garvey confronted Sutton with a copy of it in the locker room of Shea Stadium, where the Dodgers were playing a series against the New York Mets. When Sutton affirmed that the quotes were his, the two got into a brawl. Garvey threw Sutton into Tommy John's locker, causing 96 baseballs John had been signing to fall out. Neither was hurt and the two managed to overcome their feud, making sure they were the first to congratulate each other on the field for the rest of the season.[25]

With the Dodgers, Garvey played in 1,727 games over 14 seasons and hit .301 with 211 homers and 992 RBI.[18] He was selected to eight All-Star Games and won the All-Star Game MVP Award for the 1974 and 1978 games.[18] He also won four straight Gold Glove Awards from 1974 to 1977, won the 1981 Roberto Clemente Award, and finished in the top 10 in the NL MVP Award voting five times.

After Garvey signed with the San Diego Padres in 1982, the Dodgers kept his number 6 out of circulation for 21 years until it was given to utility player Jolbert Cabrera in 2003. It is Dodger policy not to officially retire a number unless a player who spent a majority of his playing days with the franchise gets inducted into the Hall of Fame.

San Diego Padres

[edit]In December 1982, Garvey signed with the Padres for $6.6 million over five years in what some felt was a "masterstroke" to General Manager Jack McKeon's effort to rebuild the team.[26] Though San Diego had vastly outbid the Dodgers, McKeon noted Garvey's value in providing a role model for younger players.[27] Additionally, Garvey's "box office appeal"—his impending departure from the Dodgers provoked some Girl Scouts to picket the stadium—helped San Diego increase its season ticket sales by 6,000 seats in Garvey's first year.[28] Sports Illustrated ranked the signing as the 15th best free agent signing ever as of 2008.[29]

His first season in San Diego allowed him to break the National League record for consecutive games played, a feat that landed him on the cover of Sports Illustrated as baseball's "Iron Man".[30] In an unusual homecoming, Garvey tied the record in his first appearance back at Dodger Stadium in Padre brown.[31][32] For breaking the record, he was named the National League Player of the Week. The streak ended at 1,207 consecutive games played (from September 3, 1975, to July 29, 1983) when he broke his thumb in a collision at home plate against the Atlanta Braves. It is the fourth-longest such streak in Major League Baseball history.

It was Garvey's second season in San Diego, however, that would be his highlight in a Padres uniform. In 1984, Garvey became the only first baseman in MLB history to commit no errors while playing 150 or more games.[33] He handled 1,319 total chances (1,232 putouts and 87 assists) flawlessly in 159 games for the Padres.[34][35]

Led by Garvey, who won his second National League Championship Series MVP award, the Padres won their first National League pennant over the Chicago Cubs in 1984.[36] In Game 4, Tony Gwynn drew an intentional walk that Garvey converted into one of his four RBIs.[36] After getting hits in the third, fifth, and seventh innings, Garvey capped off his efforts with a two-run walk-off home run off Lee Smith in the ninth inning.[36] As he rounded third base, Garvey was met by fellow Padres who later carried him off the field in celebration.[36]

The home run became popular among San Diego Padres fans and was captured in a sequence of three shots by Padres team photographer Martin Mann. He was the only photographer to get a sequence of shots of the swing, and went on to sell limited edition series photos of "The Home Run", along with appearances on local television. In an interview with The San Diego Union Tribune, Martin Mann said, "It was like nothing I've ever seen at a baseball game. It was just a magical night. There was something about that night, I don't know what it was. It felt like something was going to happen."[37]

Garvey's career spanned from 1969 to 1987.[18] He made his final appearance in a game on May 23, 1987, pinch-hitting for Lance McCullers in the ninth inning and flying out.[38] In his 19-year MLB career, Garvey was a .294 hitter with 272 home runs and 1,308 RBI in 2,332 games played.[18]

Hall of Fame candidacy

[edit]During his 15 years (1993–2007) on the National Baseball Hall of Fame ballot of the Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA), Garvey failed to reach the 75% required for induction. His highest percentage of votes was 42.6% in 1995; he received 21.1% in his final year on the ballot.

He was considered by the Hall of Fame's Expansion Era Committee (for the 1973–present era) in voting for 2011 and 2014 and was not elected. In 2017, he was on the 10-candidate ballot that was considered by the Hall's Modern Baseball Era Committee (for the 1970–1987 era) in voting for 2018 and fell short of the 75% threshold. In the December 2019 voting by the Modern Baseball Era's 16-member committee for the 2020 Hall of Fame class, Garvey received six votes (37.5%).[39] He appeared on the Classic Baseball Era Committee's 2025 ballot; the results of the ballot will be announced on December 8, 2024.[40]

Post-baseball career

[edit]In 1983, Garvey started Garvey Media Group while playing for the Padres. Its strength was in sports marketing and corporate branding.[41] In 1988, he headed Garvey Communications, mainly involved in television production including infomercials. In addition, he did motivational speaking for corporations.[41]

Garvey currently serves as a member of the board of the Baseball Assistance Team, a non-profit organization dedicated to helping former major league, minor league, and Negro League players through financial and medical hardships.[42]

Garvey played himself on an episode of the NBC sitcom Just Shoot Me!, and could also be seen in infomercials for products such as Fat Trappers and Exercise in a Bottle in 1999.[43] Both supplements were produced by Enforma Natural Products of Encino, and both were involved in controversy, with both Sonoma and Napa counties in California filing lawsuits against the company.[44]

On September 1, 2000, Garvey and his management company, Garvey Management Group, were charged by the Federal Trade Commission in the United States District Court for the Central District of California for false advertising related to a weight-loss product.[45] In 2004, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that Garvey was not liable for the content of the infomercials as he was merely a spokesman. He had earned $1.1 million for appearing in the advertisements.[46]

Garvey has mainly pivoted to being a spokesman, motivational speaker, and hosting meet and greet events to sustain himself post-baseball, but has had a variety of financial troubles, including millions of dollars of liens against his properties. The Dodgers fired him in 2011 from their marketing department when he went public with his intent at being part of an ownership group to buy the team if it was up for sale.[47][48]

2024 U.S. Senate campaigns

[edit]On October 10, 2023, Garvey announced that he was running in the 2024 United States Senate elections in California as a Republican.[49][18] Garvey sought the Senate seat that was held by Democrat Dianne Feinstein from 1992 until her death in 2023; following Feinstein's death, Democrat Laphonza Butler was appointed to the seat by California Governor Gavin Newsom subject to a partial term special election to fill Feinstein's remaining term. In the March 2024 top-two primary Garvey advanced to the November election for the term starting in January 2025 facing Democratic U.S. Representative Adam Schiff, the first-place candidate by only 3,478 votes.[3] Garvey won the partial term special election primary to replace Laphonza Butler with that term ending in January 2025, but lost to Schiff in the November election.[50]

Political positions

[edit]Garvey voted for Donald Trump in the 2016, 2020 and 2024 presidential elections.[51] In April 2024, Garvey repeatedly called college students protesting the war in Gaza, "terrorists".[52] He encouraged law enforcement to take action against the anti-war protestors, but his comments came the day following arrests at universities across the U.S.[52] He claimed that interruptions to and obstruction of education are an act of terrorism.[52]

Personal life

[edit]

At age 22, Garvey married Cynthia Truhan[53] in 1971. They had two daughters, Krisha and Whitney.[54] Truhan left Garvey for composer Marvin Hamlisch; Garvey was already romantically involved with his secretary, which Truhan didn’t find out until after she had left him.[53] Garvey and Truhan divorced in 1985.[55]

In July 1988, Garvey discovered that Cheryl Moulton was pregnant with his child, Ashleigh Young.[53] Despite this, Garvey proposed to Rebecka Mendenhall in November 1988, telling Mendenhall about Moulton at the time of the proposal. Mendenhall learned that she was pregnant that January. Garvey broke their engagement January 1, 1989.[55] Garvey and Mendenhall had been in a long-distance relationship since 1986. Their only child, a son named Slade Mendenhall, was born in October 1989.

Garvey said he was in the midst of what he termed a "midlife disaster".[53] Garvey sued his ex-wife, Truhan, for access to his two children when she had denied it, which he won. His daughters testified in court that they did not wish to see him, but a psychiatrist testified that they exhibited parental alienation syndrome. During the 2024 campaign, Garvey's oldest daughter Krisha stated that he cut contact with her 15 years ago while Young and Mendenhall also came out and stated Garvey had not made the effort to speak with them outside of contact placed via family court.[53][56]

In January 1989, Garvey became engaged to Candace Thomas, whom he met at a benefit for the Special Olympics. Over the next few weeks, Garvey and Thomas began a courtship that included trips to the inauguration of President George H. W. Bush and the Super Bowl.[53] Garvey and Thomas were married on February 18, 1989. They have three children together and four children from previous marriages. Garvey resides in Los Angeles and Palm Desert, California.[57]

Honors

[edit]- Steve Garvey Junior High School (1978), in Lindsay, California, was named for him, but was eventually renamed as part of Reagan Elementary in 2011.[58]

- In 1981, Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig included him in their book The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time.

- Garvey's jersey No. 6, worn during his entire MLB career, was retired by the Padres on April 16, 1988.

- California Sports Hall of Fame (2009)

- Irish American Hall of Fame (2009)

- Michigan State University Athletics Hall of Fame (2010)[59]

- Garvey's jersey No. 10 was retired by Michigan State in 2014.[17]

- He was selected to the initial class of "Legends of Dodger Baseball" in 2019.[60]

See also

[edit]- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- Major League Baseball consecutive games played streaks

References

[edit]- ^ "The all-time All-Star Game starting lineup". MLB.com. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- ^ McCarthy, Colman (December 20, 1981). "No Greater Love has no greater friend at Yuletime than Dave Butz". Arizona Daily Star. Vol. 140, no. 354. The Washington Post. p. C3. Retrieved October 17, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Riquelmy, Alan (April 12, 2024). "California certifies March 5 primary election results". Courthouse News Service. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ "Democrat Adam Schiff wins California's U.S. Senate race". Los Angeles Times. November 6, 2024. Retrieved November 6, 2024.

- ^ "Steve Garvey Baseball Stats | Baseball Almanac".

- ^ Boyer, Peter J. (September 24, 1989). "The Intimate Steve Garvey: The Former Dodger Hero Tells How His Perfect Life Became a Perfect Nightmare". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ "Dodgers go green". March 17, 2012.

- ^ Totem Yearbook. Tampa, Florida: Chamberlain High School. 1966. p. 225.

- ^ Smith, Marc (June 15, 1977). "Expos' Call Relieves Tom". Florida Today. p. 1C. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Johnston, Joey (April 21, 2017). "Legacy Gala looks to enlist alumni in restoring Chamberlain's luster". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved June 19, 2019 – via www.tampabay.com.

- ^ "Steve Garvey | Video Library". Lansing State Journal. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "MSU Athletics Hall of Fame Class of 2010: Steve Garvey – Michigan State Official Athletic Site". Msuspartans.com. September 29, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ "Steve Garvey | Video Library". Lansing State Journal. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ Kahn, Alex (April 18, 1971). "Garvey Feels He'll Stay". Standard-Examiner. Ogden, UT. United Press International. p. 8D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Padres' Garvey remembers paying visit to Tigers' Den". The Commercial Appeal. Memphis, TN. October 13, 1984. p. D3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Steve Garvey has jersey retired at Michigan State on Sunday". True Blue LA. January 25, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "MSU baseball Q&A: Steve Garvey's Spartan stint a '10'". Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Baseball MVP Steve Garvey running for California Senate Seat". Washington Post. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ "New York Mets at Los Angeles Dodgers Box Score, September 1, 1969". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Steve Sax – Los Angeles Dodgers Steve Sax". Losangelesdodgersonline.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ Schroeder, W. R. Bill. "The Durable Dodger Infield". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ John, Tommy; Valenti, Dan (1991). TJ: My Twenty-Six Years in Baseball. New York: Bantam. pp. 164–165. ISBN 0-553-07184-X.

- ^ John and Valenti, p. 165.

- ^ Boswell, Thomas (August 17, 1978). "'Best Reggie' Leads 5-4 Dodger Win". The Washington Post.

- ^ John and Valenti, 183–84.

- ^ Maisel, Ivan (April 4, 1983). "San Diego". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Steve Wulf (April 25, 1983). "Incredibly, Steve Garvey's return to L.A. as a Padre – 04.25.83 – SI Vault". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ Wulf, Steve (April 25, 1983). "It Was Too Good To Be True". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Heyman, John (May 15, 2008). "What a deal!". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 19, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ "Steve Garvey, Baseball, San Diego Padres – 04.25.83 – SI Vault". Sports Illustrated. April 25, 1983. Archived from the original on August 9, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ Steve Wulf (April 25, 1983). "It Was Too Good To Be True – 04.25.83 – SI Vault". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ "Garvey Sets a League Record". The New York Times. Associated Press. April 17, 1983. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ "Error Records by First Basemen". www.baseball-almanac.com.

- ^ "Steve Garvey Career Stats at Retrosheet". retrosheet.org. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "1984 Regular Season Fielding Log For Steve Garvey". retrosheet.org. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Steve Wulf (October 15, 1984). "You've Got To Hand It To The Padres". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ Kirk, Kenney (February 27, 2021). "San Diego Stadium farewell: Garvey's '84 homer remains Padres' — and city's — most memorable sports moment". San Diego Union Tribune.

- ^ "Montreal Expos at San Diego Padres Box Score, May 23, 1987". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Castrovince, Anthony (December 8, 2019). "Miller, Simmons elected to HOF on Modern Era ballot". MLB.com. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Classic Baseball Era Committee Candidates Announced". baseballhall.org. November 4, 2024. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "Steve Garvey's Biography - Book Steve Garvey for a Speaking Engagement".

- ^ "Baseball Assistance Team Board and Operations". MLB.com. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ Henderson, Joe (December 20, 1999). "It's hip to be square for Garvey". Tampa Bay Times. Vol. 105, no. 303. p. Sports 1. Retrieved October 17, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hellmich, Nanci (August 20, 1999). "Diet supplements' claims anger consumer watchdogs". The Times. Vol. 128, no. 265. p. 1D. Retrieved May 29, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "FTC Files Charges Against Additional Defendants Involved in the Deceptive Advertising of "The Enforma System"". Federal Trade Commission. September 1, 2000. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ "Ninth Circuit: Steve Garvey Not Liable for Hawking Weight Loss Program". Metropolitan Newspaper Service. September 2, 2004. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Shultz, Alex (May 29, 2024). "Steve Garvey's bizarre Senate campaign: I think I figured out why he's really running". Politics. Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. OCLC 728292344. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Dodgers fire Garvey from front-office position". ESPN.com. July 9, 2011. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ Mehta, Seema (October 10, 2023). "Former Dodgers star and Republican Steve Garvey enters U.S. Senate race". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ Martinez, Xavier (November 13, 2024). "Adam Schiff Defeats Steve Garvey in California Senate Race".

- ^ Kevin Rector (October 3, 2024). "Your guide to California's U.S. Senate race: Garvey vs. Schiff". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c Korte, Lara; Venteicher, Wes (April 25, 2024). "California Senate candidate Steve Garvey calls student protesters 'terrorists'". Politico. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Reilly, Rick (November 27, 1989). "America's Sweetheart". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ John and Valenti, p. 183.

- ^ a b Chin, Paula; Rebelo, Kristina (March 13, 1989). "In the Game of Love, Steve Garvey Plays the Artful Dodger". People.

- ^ "Steve Garvey touts 'family values' in his Senate bid. Some of his kids tell another story". Los Angeles Times. February 1, 2024. Retrieved August 7, 2024.

- ^ Schrotenboer, Brent. "Revisiting the Padres of '84". SignOnSanDiego.com. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ "Year in Review - The Sun-Gazette Newspaper". www.thesungazette.com. January 4, 2012.

- ^ "MSU Athletics Hall of Fame inducts 10 new members". Msu Athletics Hall of Fame Inducts 10 New Members - the State News. The State News. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ "Maury Wills named to 'Legends of Dodger Baseball'". MLB.com. April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Steve Garvey at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Steve Garvey at IMDb

- Steve Garvey for U.S. Senate

- 1948 births

- Albuquerque Dodgers players

- American athlete-politicians

- American people of Irish descent

- Baseball players from Tampa, Florida

- California Republicans

- George D. Chamberlain High School alumni

- Gold Glove Award winners

- Living people

- Los Angeles Dodgers players

- Major League Baseball All-Star Game MVPs

- Major League Baseball broadcasters

- Major League Baseball first basemen

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- Michigan State Spartans baseball players

- Michigan State Spartans football players

- National League All-Stars

- National League Championship Series MVPs

- National League Most Valuable Player Award winners

- Ogden Dodgers players

- San Diego Padres players

- Spokane Indians players

- Candidates in the 2024 United States Senate elections